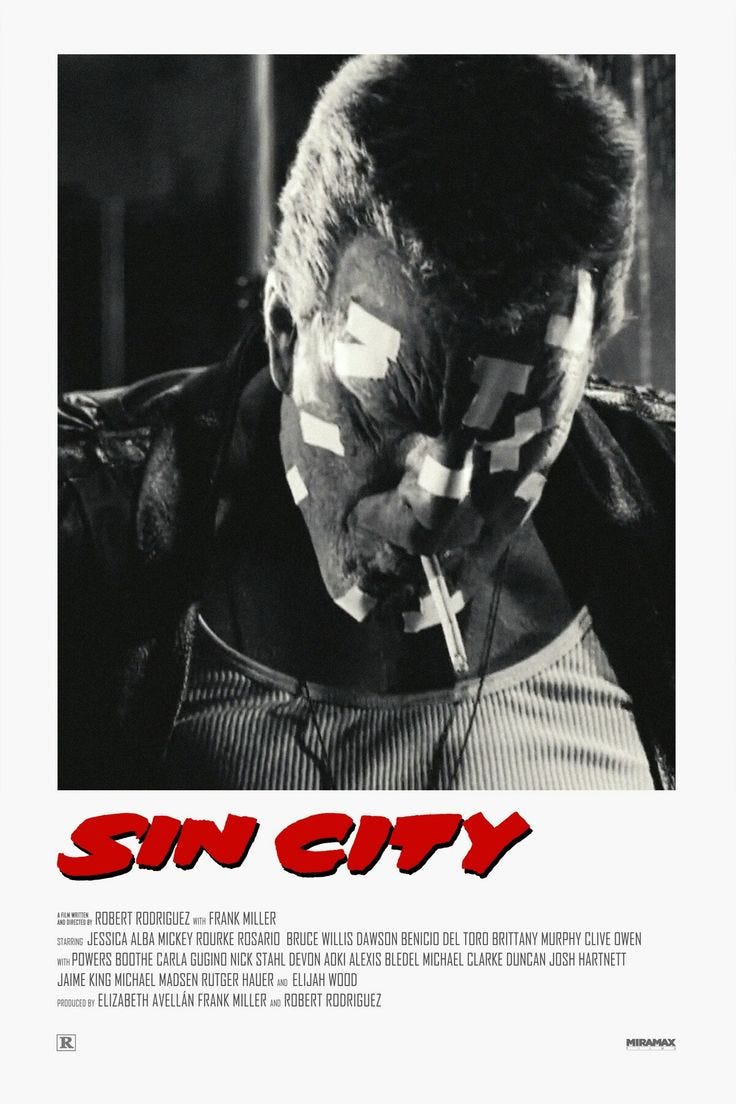

Sin City

A Maintenance Economy

Walk down the right back alley and the city tells you who it’s for.

Not with speeches. Not with plans. With posture. With the way the light refuses your face and keeps someone else intact. With rain that never cleans anything, only redistributes what’s already been decided.

This is a city that doesn’t hide its violence. It organizes it. Frames it. Cuts around it. You don’t stumble into Sin City. You’re sorted.

The camera already knows where you rank.

Men narrate because the city doesn’t.

Or because it doesn’t need to.

It lets them talk themselves into coherence while it moves bodies through shadow like inventory. Confessions arrive late. Mercy arrives misfiled. Justice shows up wearing the wrong coat and stays just long enough to feel exceptional.

Every story here begins after the decision has been made,

never by the people living inside it.

The streets are not dangerous. They’re instructional.

You just don’t get the lesson until it’s over.

A woman falls. A man remembers her wrong. Another man remembers her too well. Somewhere a badge is still warm from the last hand that held it like a promise. Somewhere else a fist is already mid-swing, relieved of responsibility.

This is not a movie about corruption. Corruption implies deviation. Sin City is about maintenance.

Two janitors work the same night shift. One carries a badge and a hospital bracelet. One carries a blade and a name nobody will write down. They never meet. They don’t need to. The floors stay clean either way.

The city prefers it that way.

Don’t ask who runs this place. Ask who gets cleaned up afterward.

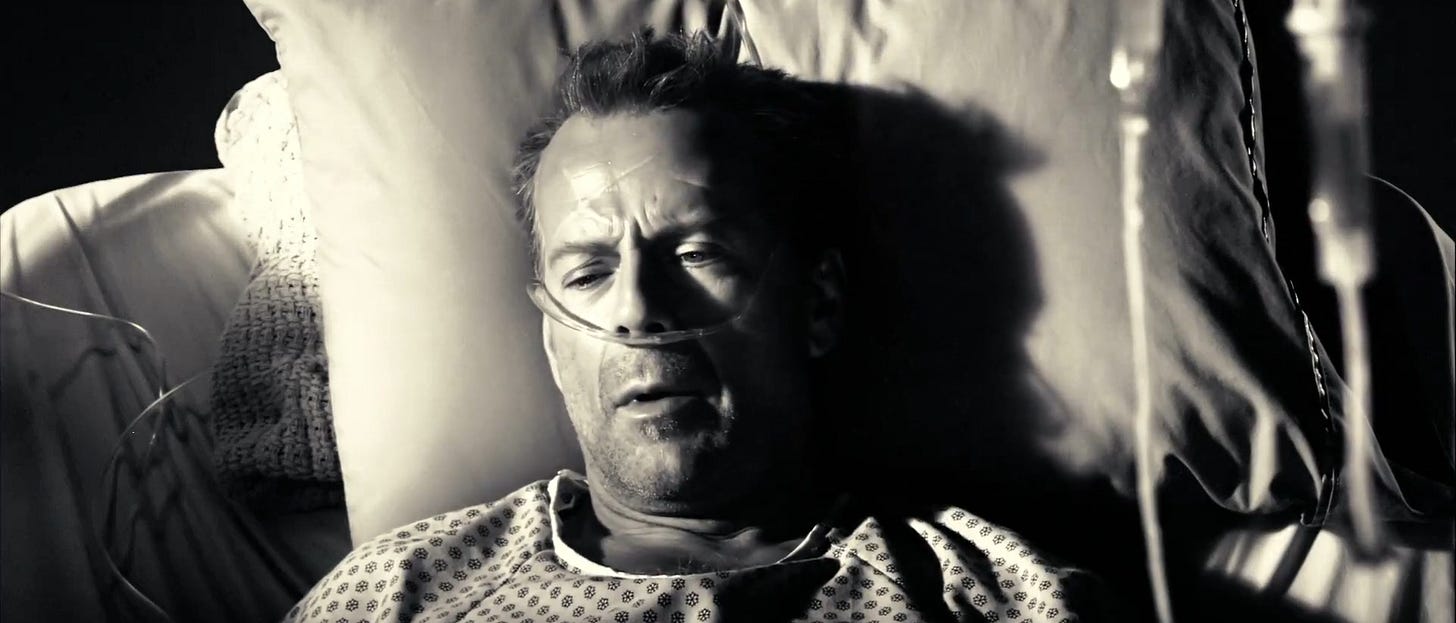

Hartigan believes in lines.

Not moral ones. Procedural ones. The kind you can point to on a form, in a hallway, on a body. He believes there is a place where things stop being his responsibility, and that belief is the only thing keeping him upright.

The badge doesn’t make him righteous.

It makes him legible.

When Hartigan moves through the city, the frame tightens, not to grant intimacy but to certify function. He is always shown doing his job. Even when the job is unbearable. Even when the cost is permanent. The film gives him dignity by giving him inevitability. He does not choose. He complies.

That’s the trick.

Hartigan’s goodness is real, but it is beside the point. The system does not require goodness. It requires credibility. His age, his fatigue, his failing heart are not obstacles. They are credentials. They tell us this violence has history. That it has paid dues. That it has earned the right to continue.

The city prefers him horizontal.

Hospital bed. Interrogation chair. Bathroom floor.

Suffering becomes evidence of seriousness. Pain becomes the receipt.

The city favors men like this. Not because they resist it, but because they make it feel expensive.

Hartigan does not bend the law. He carries it until it snaps inside him. That distinction matters. He is never framed as corrupt. He is framed as cornered. Which is much more flattering.

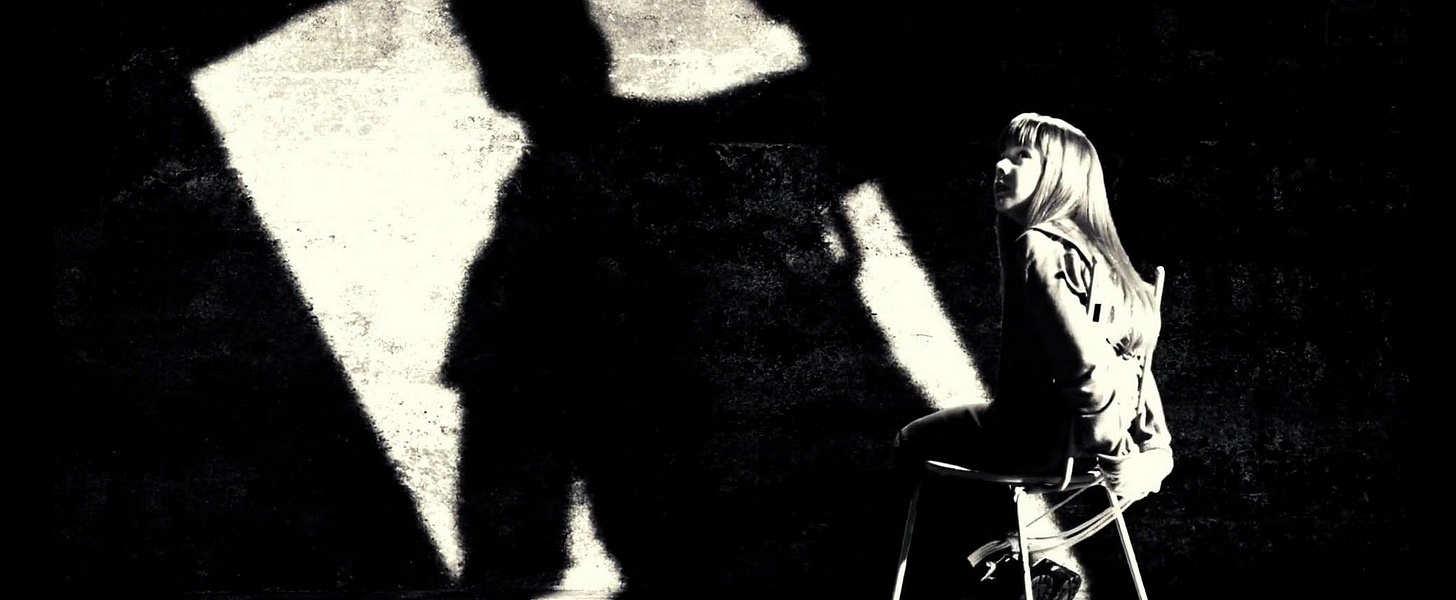

This is where Nancy enters, not as a person, but as a state to be preserved.

As a child, she supplies immediate proof. Still clean. Still intact. The rescue succeeds not only in removing danger, but in securing a condition. Safety matters, but purity is what validates the burden. Her words arrive like certification, and the system accepts them.

The years between are managed carefully. Letters maintain distance. Time is allowed to pass without being acknowledged. The girl remains eleven in the only economy that matters. Hartigan does not want her. He wants the world where wanting her never becomes necessary.

Her untouchedness becomes the last clean line he can still draw. Her safety retroactively justifies every compromise he has already made. She is not a future. A preserved condition that allows restraint to keep meaning in a city that rewards none of it.

As an adult, Nancy returns with agency. With desire. With reciprocity. She offers closure on her own terms. The frame presents her body slowly, reverently, as invitation. The city insists we see what has grown.

Hartigan refuses.

This is why the Yellow Bastard matters.

Junior Roark does not oppose Hartigan. He externalizes him.

Where Hartigan narrates restraint, Junior performs entitlement. Where Hartigan needs purity to remain intact, Junior needs it to scream. They are not opposites. They are adjacent outcomes of the same economy. One sanctified. One obscene.

The film allows Hartigan to kill Junior easily.

The body collapses. Violence works. The contamination is removed.

But the father remains.

Hartigan can kill the son because the son is framed as offense. He cannot kill the Senator because the Senator is framed as structure. The distinction is not material. It is ideological.

This is the line Hartigan stands on without naming it. The last place where violence still pretends to be accountable.

This is where Shlubb and Klump arrive.

They enter without ceremony. No badge. No paperwork. No narration. Just flesh assigned a task. The frame does not linger because it does not need to. Nothing requires justification.

When Hartigan bleeds, the violence must mean something. When Shlubb and Klump swing, it doesn’t. One kind of harm requires a story. The other requires only permission.

They do not defeat him.

They replace him.

Not as men, but as logic.

After they pass through, Hartigan feels older. Not because of what they did, but because of what they reveal. The city does not need men like him to enforce its will. It needs them to explain it.

Confession becomes his final service.

The close-ups arrive gently. Too gently. The face fills the frame as if endurance itself were a moral act.

Hartigan does not end the system.

He exits it cleanly.

He removes himself as a claimant. He withdraws from the economy he can no longer survive inside. His body becomes the final boundary he can still enforce.

The dynasty remains untouched.

When he is gone, the floor is clean.

The city moves on, relieved of the inconvenience of conscience, having learned once again that suffering is easier to manage than justice.

State power does not need monsters.

It needs men who will carry the burden until it can be set down quietly, somewhere out of sight.

Hartigan does that.

Faithfully.

He watches all of it from above.

Not because he cares, but because someone has to mark the rhythm. Desire. Punishment. Erasure. He opens the story. He closes it. He never stays long enough to be implicated.

The Man doesn’t bleed. He doesn’t confess. He doesn’t preserve anyone. He observes the pattern and knows when to step aside.

Men charge forward believing they are exceptions. Knights. Saviors. Necessary sacrifices. The city accepts the gesture and keeps nothing they offer.

Purity is preserved. Authority is laundered. Violence is redistributed.

The Man lights the match. The Man walks away.

Someone will always believe they’re the last one who has to do this.

The city lets them.

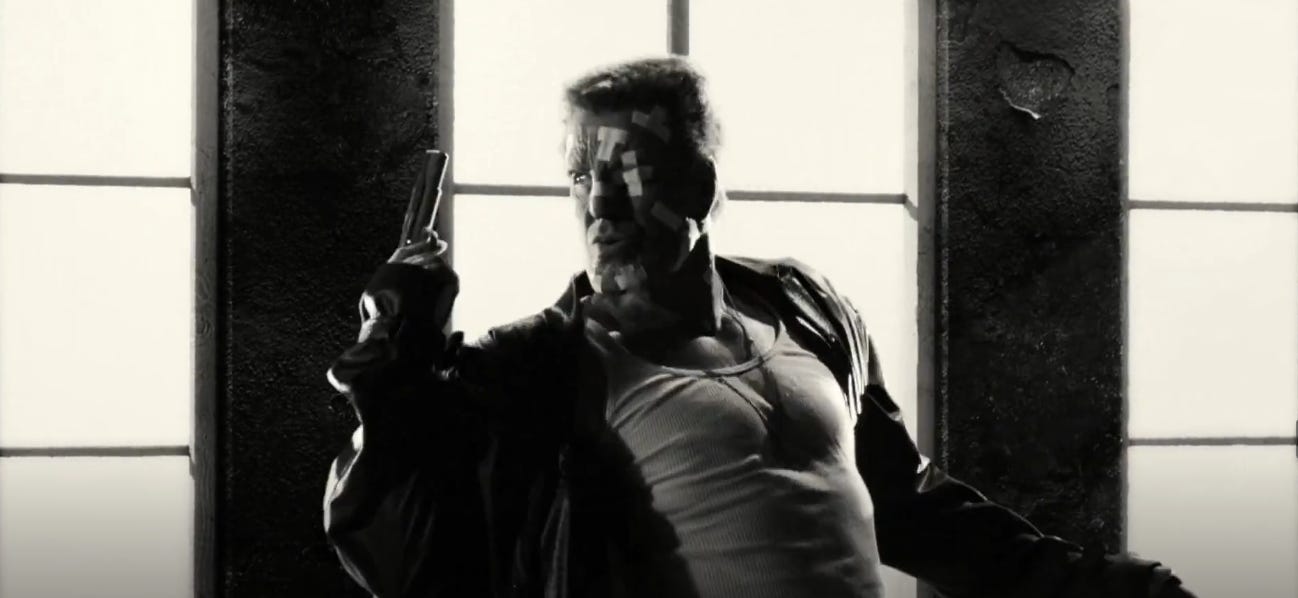

Marv is not interested in lines.

He doesn’t believe in them. He steps over them without noticing, not because he’s rebellious, but because they were never built for him. Procedure slides off his body. Paperwork can’t hold his weight.

Where Hartigan is legible, Marv is undeniable.

The city does not certify him. It endures him.

The frame treats him differently. It doesn’t sanctify. It corrals. Wide shots give him room not out of respect, but necessity. Close-ups don’t arrive to honor suffering; they arrive to inventory damage. His face is a map of consequence, already overdrawn.

Marv moves like someone who has already been sentenced.

He is often mistaken for chaos. That’s convenient. Chaos implies accident. Marv is not an accident. He is what happens when the city produces a body capable of absorbing punishment and then gives it something to love.

His room tells the rest of the story.

It looks less like a fortress than a childhood paused mid-gesture. A toy airplane. A Bible kept open like a rulebook, not a comfort. The windows turn the room into a cell. Bars without bars. He is out of pills. Whatever kept him regulated is already gone. The city did not give him language for growing up. It gave him containment instead.

Goldie is not his salvation. She is his assignment.

Marv does not fall in love the way the city understands love. There is no future in it. No preservation. No purity to guard. What he offers is not protection, but completion. When Goldie is taken from him, the circuit closes. There is nothing left to manage, only to finish.

Where Hartigan believes suffering proves something, Marv believes suffering ends something.

The city lets him believe this because it is useful.

Lucille tries to keep him alive without making him useful. Pills. Warnings. Boundaries. Care without mythology. She does not ask for confession or sacrifice. She asks him to survive.

The city does not tolerate this.

She is tortured by Kevin. She is killed by police already in Roarke’s pocket. Care that cannot be converted into outcome is removed.

Marv’s violence does not need laundering. It arrives already disqualified. No one needs to pretend it is ethical. That freedom is its own containment. He can kill anyone, as long as the city never has to see itself doing it.

He is hidden power not because he operates in secret, but because his outcomes do not threaten legitimacy. Bodies fall. Order remains intact.

The city routes him carefully.

Basements. Back rooms. Alleys without names. Places where the frame grows cavernous and the light collapses into extremes. The world simplifies around him. Black or white. Alive or finished. The city does this for him. It makes his work possible by narrowing the question.

The city produces monsters that don’t speak, and monsters that won’t stop.

Against Kevin’s silence, Marv cannot stop speaking.

Even faith collapses under pressure.

The priest spits on Goldie’s body before giving up the Cardinal’s name. Judgment first. Cooperation second. The order matters. Under strain, sanctity becomes routing. Sin is assigned downward. Protection moves up.

Marv does not seek justice. He seeks accuracy.

That is why the threat works.

Roarke does not argue with him. He names Marv’s mother. Not as revenge, but as leverage. The Farm does not need a trial. Kevin does not need a confession. The city only needs Marv to stop resisting accuracy.

He does.

Not because he is guilty, but because care, once found, is easier to weaponize than fear.

Marv remembers Goldie perfectly. Not as a future, not as a symbol, but as a moment that felt true. That memory is enough. It does not ask to be protected. It asks to be honored through action.

This is where Marv becomes dangerous.

His devotion is pure in a way the city never is. There is no transaction in it. No attempt to remain clean. No fantasy of leaving something untouched. He does not preserve. He avenges. He destroys in order to keep the memory intact, not the body.

Marv looks at Nancy without hunger.

The camera never does.

The city insists we see what he refuses to claim.

The frame indulges his brutality. Stylizes it. Gives it weight and clarity. Violence becomes choreography. Impact becomes meaning. The city allows this because Marv’s excess never threatens continuity. He clears space. He never claims it.

When Marv is caught, the system does not need to be clever. It does not need to replace him. It simply absorbs him. His body was always the endpoint. The punishment feels enormous only because his capacity was enormous.

His death satisfies something the city cannot name.

Not justice.

Closure.

Marv does not misunderstand the city. He understands it too well. He knows there is no exit, no redemption. That knowledge frees him from pretending.

If Hartigan believes the city can be persuaded to mean something better, Marv knows it can only be answered.

And so he answers it in the only language left to him.

With his body.

With everything.

When Marv is gone, the city does not need to clean very much. His violence was already accounted for. The mess was expected. The cost was priced in.

The street looks the same.

Old Town does not ask for permission.

It enforces boundaries.

A man crosses the line and the response is immediate. No speech. No warning. The correction arrives fast enough that it feels procedural. This is not safety. It is jurisdiction asserted without apology.

Rules exist because explanation wastes time.

No cops.

No freelancing.

No lingering once a decision is made.

Authority here moves through coordination, not charisma. Commands shorten the room. Disagreement ends quickly. Violence is not expressive. It is corrective.

Miho appears without announcement. She does not posture or narrate. She does not need consensus. She moves, finishes the task, disappears.

Silence functions as efficiency. Meaning never piles up around her because it doesn’t have to. The blade moves so the logic doesn’t.

Elsewhere, the frame indulges. Here, it measures.

Shots widen. Bodies are placed in space with clarity. Light flattens. Conflict becomes visible from all sides, which means it resolves faster. Desire does not drive the camera. Outcomes do.

A mistake is made and corrected without ceremony. A body drops and the response is logistical. Removal. Containment. Reset. Nothing is allowed to escalate into legend.

This is not mercy.

It is management practiced without myth.

Old Town holds because violence is expensive here and immediately accounted for. There is no patience for buildup, no room for martyrs. The city tolerates this place because it works. Not ethically. Operationally. Everything else can pretend brutality is accidental because Old Town keeps it scheduled.

Autonomy here is conditional and enforced collectively. The women do not wait to be protected. They establish terms and make violation costly. Control looks like calm because the rules are already in motion.

When authority is interrupted, time compresses. Discipline frays. The gap is punished quickly. Not because the rules failed, but because they were paused. The city moves fastest when order hesitates.

Old Town does not threaten the city.

It embarrasses it.

It proves that violence could have been governed instead of romanticized. That boundaries could have replaced stories. That silence could have done the work narration keeps failing to finish.

The city does not learn from this.

It lets the boundary hold just long enough to remain useful, then looks for a way to move past it without changing anything else.

When someone steps back into the rest of Basin City from here, they carry no revelation. Only a lesson.

Process works.

Stories don’t.

And the city is always happier with the man who understands that difference.

Dwight believes in adjustment.

Not lines. Not vows. Angles. Reflections. He survives by knowing where to stand and when to move. He is always mid-correction, always improving the story he tells himself about what just happened.

Where Hartigan is authorized and Marv is endured, Dwight is tolerated.

The city does not need to certify him. It needs him to manage things.

The frame understands this. Mirrors matter. Windows matter. Glass that lets him check whether he’s still intact. Dwight is constantly confirming his outline, making sure the man he thinks he is still fits inside the shape the city allows.

Dwight’s violence is not devotional. It is corrective.

He doesn’t want to finish anything. He wants to fix it. Put it back where it belongs. Get the mess aligned so it stops asking questions. This is why he lasts longer than the others. This is why the city keeps him around.

Jackie Boy makes this visible.

Jackie Boy is sloppy violence, loud, entitled, unsecured. He hits Shellie in the shadows, offhand, like a habit that doesn’t need witnesses. The camera barely reacts. This kind of harm is already priced in.

Dwight does not stop Jackie Boy because it’s wrong. He stops him because it’s inefficient.

When Dwight slaps Gail, it happens in the light. The frame clears space for it.

The violence is presented as a corrective gesture, sharp, contained, regrettable in tone but necessary in function. Manute’s violence follows differently: force without apology, order without pretense. State muscle asserting jurisdiction.

Three slaps. Three permissions.

The film does not ask you to weigh them equally. It asks you to understand their placement.

Dwight believes noticing harm is the same as preventing it. He believes calibration is care. The frame indulges this belief. It gives him time to look conflicted. It gives him dialogue. It gives him just enough self-awareness to feel ethical without ever becoming accountable.

This is how Dwight survives.

He reroutes violence the way others confess or absorb it.

Jackie Boy doesn’t need to die where he stands. He needs to be moved. Redirected. Delivered into a space where his death will register as cleanup, not disruption. Old Town becomes the sink. The girls become jurisdiction. Dwight becomes courier.

He tells himself this is strategy. He tells himself this is protection.

The city lets him believe this because it keeps the system elegant.

Dwight is careful with violence. Not moral. Logistical. Violence must remain useful. It must not call attention to itself. It must not point upward. It must not demand confession later.

He never believes he is innocent.

He believes he is necessary.

That belief is harder to kill.

When bodies accumulate around Dwight, they do so quietly. No operatic suffering. No endurance shots. Just consequences that never quite land on him directly. This is what adaptation buys you: distance.

The frame keeps him moving. Fewer still moments. No place to lie down. He does not earn the dignity of collapse or the clarity of ending. The city will not let him stop long enough to become a problem.

Dwight thinks this is freedom.

Probation doesn’t usually announce itself.

He will keep adjusting.

Keep surviving.

Keep telling himself the next correction will hold.

The city will let him.

It always does.

What the city cannot manage is not purity.

Not sacrifice.

Not adjustment.

What it cannot manage is what refuses to be finished.

Wild love does not preserve.

It does not correct.

It does not clean.

Gail does not belong to Dwight.

Dwight does not finish anything for her.

They remain misaligned, sovereign and orbiting, and that misalignment is the point. Possession would make it legible. Closure would make it safe.

In a city where the camera blesses violence, wild love never quite fits the frame.

Always mine.

Always.

And never.

By morning, the city looks the same.

That’s how you know the work was done.

Hartigan is gone. Not cleared. Not corrected. Gone. The record holds. The badge cools. A file closes without opening anything else. State power remains intact, relieved of the inconvenience of explanation. The story says he chose this. The city prefers that phrasing. Choice sounds voluntary. It sounds moral. It sounds like the system didn’t have to lift a finger.

Marv is gone too. Louder on the way out. Bloodier. Useful. He removed what could be removed. He took out the liabilities that operated in the dark. He cleaned the rooms no one wanted listed on the blueprint. Then he sat down where he was told and finished the job by confessing to more than he did. The investigation ends clean because he made it so. The dynasty survives because he never reached it.

Dwight is still moving.

That’s his function.

He doesn’t disappear. He doesn’t confess. He reroutes. Adjusts. Keeps the mess from pooling where it can be noticed. He learns which doors stay open and which faces can be replaced. The city doesn’t reward him with peace. It rewards him with continuity. That’s better for business.

The winners do not bleed.

The Roarks remain. Not because they are stronger, but because they are framed as untouchable. Not guarded by armor or men, but by belief. The belief that state power is a different substance. That it can’t be met the same way. That violence stops somewhere before it reaches the office with the good lighting.

Bodies are shown that can be broken. Others are kept intact by framing alone. The rule is never tested. The mystification holds.

So the janitors do their rounds.

One launders the story so it can be believed again.

One clears the back rooms so the smell doesn’t travel.

They don’t meet. They don’t need to. The floors stay clean either way.

This is not corruption. Corruption would suggest deviation. This is maintenance. Scheduled. Rehearsed. Blessed by the frame that knows where to look and where not to linger.

By the time the credits roll, the city has what it wants: order without justice, continuity without truth, violence without accountability. The bodies are gone. The structures remain.

The analysis doesn’t stop when the credits roll. The real work happens in the alley, after the lights come up. Follow me into the next shadow.

Works Cited / Sources Consulted

This essay draws on the following primary and contextual materials. Citations are listed for transparency, not deference.

Primary Texts

Sin City (2005), directed by Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller

Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014), directed by Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller

Frank Miller, Sin City comic series (Dark Horse Comics)

Supplementary Materials

Official film screenplays and shooting scripts (where available)

DVD/Blu-ray commentaries and promotional interviews with Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller

Production stills, storyboards, and panel-to-frame comparisons released by Miramax / Troublemaker Studios

Publicly available interviews discussing Rodriguez’s digital backlot process and Miller’s narrative philosophy

Critical & Contextual References

Roman Polanski, Chinatown (1974), as a comparative noir framework

Francis Ford Coppola, Apocalypse Now (1979), for visual and theological framing of authority

Film noir scholarship on fatalism, masculinity, and institutional power

Feminist film theory addressing gaze, purity economies, and narrative containment

Media literacy frameworks concerning ideology, spectatorship, and framing

No secondary criticism is quoted directly. All interpretations are original readings grounded in the films’ visual language, narrative structure, and thematic repetition.

Acknowledgments

This essay was shaped through sustained dialogue, pressure-testing, and refusal of easy conclusions.

Thanks to the writers, critics, and readers in the Substack film community whose work treats movies not as content, but as systems worth interrogating. Especially those willing to sit with discomfort rather than resolve it.

Thanks to Mondayswife, whose request for Sin City set this examination in motion.

And to every reader who understands that close reading is not an act of fandom or contempt, but attention.

Disclaimer

This essay is not an argument against enjoying Sin City.

It is an argument against mistaking enjoyment for innocence.

The analysis presented here examines how narrative framing, visual emphasis, and character construction perform ideological work, often without announcing themselves. It critiques systems, not individual viewers, and structures, not isolated scenes.

Discomfort is not the goal. Clarity is.

If this reading unsettles your relationship to the film, that unease is part of the text’s function, not a flaw in yours.

Nothing here asks you to stop watching.

It asks you to notice what stays clean, what gets erased, and who pays for the order you’re being shown.

I think this deserves a rewatch! I don't remember any of this haha. Fun to get acquainted with it again.

I watched this a long time ago as a teen in theaters and didn’t quite understand what was going on because I didn’t realize it was a series of characters interacting with the city. Now that I see the triptych that stitches them all together and look back, well, my opinion doesn’t change much. Sin City is still amazing to this day.