Sherlock Holmes: A Board of Shadows

A Study in Sacrifice

Chess is a game of kings. The board itself insists on it: two monarchs, fragile but untouchable, while every other piece is defined by its expendability. Pawns move first, bishops cut diagonals, rooks march straight, but their lives are calculated in advance, meant to be offered, spent, cleared. Victory is not survival; it is endurance at the top while the rest of the board is stripped away.

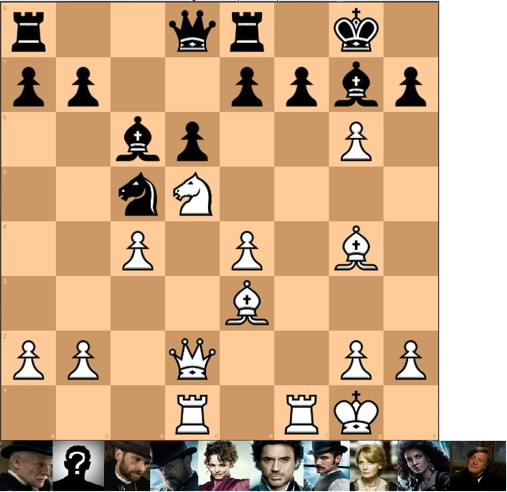

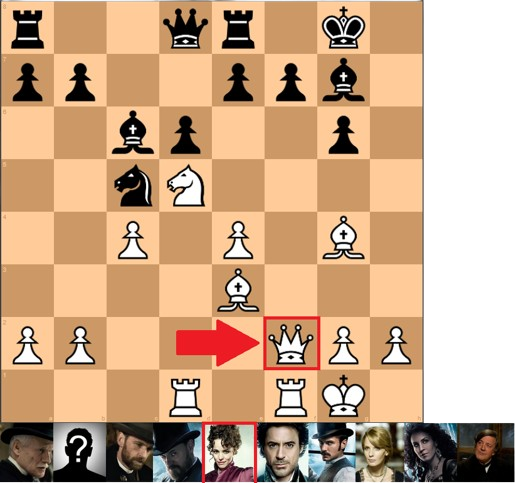

Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows leans on this metaphor openly, with its balcony chess match between Holmes and Moriarty. But the film does more than nod at strategy, it treats lives exactly as the board does. Irene Adler, Dr. Hoffmanstahl, Simza’s brother, even Holmes’s own disguises: they enter, advance, and are discarded. What looks like romance, civility, or comedy is only sacrifice masked.

I should admit my bias. Holmes has always been my favorite fictional character. I grew up with Jeremy Brett’s sharp precision as the Holmes, and Robert Downey Jr.’s restless eccentricity only extended that fascination. These films aren’t my canon, but they became my bridge, a way to keep watching how Holmes adapts, survives, and sometimes betrays his own myths.

This essay traces that logic. Through four pillars, sacrifice, illusion, broken rules, and the machine, it argues that Game of Shadows is less about a duel between geniuses and more about how the board itself erases its pawns.

Sacrifice as Strategy

Holmes tells Moriarty at the balcony board:

“A winning strategy sometimes necessitates sacrifice.”

The line is literal, but it is also the grammar of the film. Every major figure around the kings is advanced, spent, erased. The board is never equal; it is prepared ground where pawns are already gone.

In the first film she declared, “I belong to no one.” Here that autonomy is staged as silence: reframed as respect, but already calculation. His later betrayals, throwing Mary from a train, manipulating Watson, using Simza, prove he respects no boundaries. His silence is not reverence. It is strategy. The camera keeps its intimacy for Holmes, not Adler. When she dies, we see his anguish in close-up, not her end. Her loss becomes his evidence, his motivation, not her memory. Holmes spends her, the queen ceded early, sacrificed to strip Moriarty’s cover. But her absence lingers like a move made too early, destabilizing the board, haunting the film as a ghost it never recovers from.

On the board it is a queen and a pawn; in the film it is Adler and Hoffmanstahl. The game names them pieces, but the story names them expendable. And this is not just plot logic, but history’s. Europe too was a prepared board, alliances locked, syndicates arming, timetables ticking toward Sarajevo. Pawns would vanish by the millions while kings called it strategy.

The same logic consumes Dr. Karl Hoffmanstahl. Rescued from a bomb only to be silenced by Moran’s dart, the surgeon serves one role, reshaping René, then is erased. The blocking confirms it: Hoffmanstahl pushed to frame edge, glimpsed in reaction, then gone. A specialist pawn: advanced for a single tactical square, cleared the moment his purpose is fulfilled.

Holmes dons yellowface, a racial mask played for laughs. Another pawn advanced for one beat, then erased. Caricature itself becomes tactical: identity reduced to mask, deployed briefly, discarded without consequence. Even racial caricature is treated as pawn logic: mimicry weaponized, identity hollowed, the “move” erased from the board.

Mary’s fate echoes the same calculus: ejected from the train in a single efficient beat. She is “rescued,” but also removed from the filmic field, cleared so the duel can proceed unencumbered. Even Simza’s agency is half-written, half-ghosted: she is permitted moments of choice, but always in service of Holmes’s larger design.

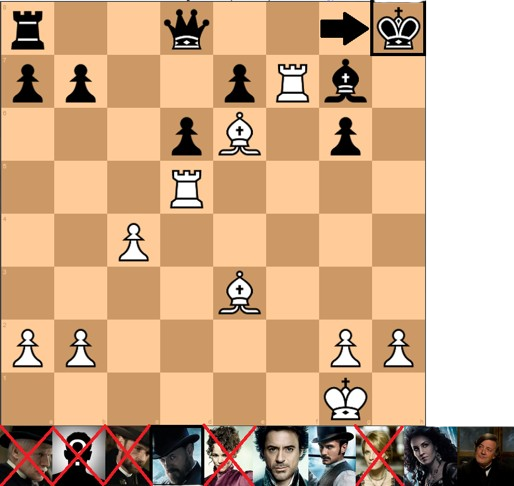

The film insists on this structure even in the climax. At the waterfall plunge, the camera privileges Holmes’s face last, calm against Moriarty’s panic. Even in supposed sacrifice, he is framed as composed, foreknowing, the owner of the moment. Zimmer’s score swells for his voice, thins for the others. The pawn’s exit is backgrounded; the king’s strategy is foregrounded.

The Illusion of Equality

Close-ups make the balcony look fair; the cut pattern hides that pawns are already trimmed from the frame. Shot/reverse-shot, measured voices, civility staged. The duel looks like symmetry. Yet the cut betrays it.

Simza moves like Holmes’s bishop, weaving through the summit hall, scanning diplomats, searching for René. Watson, the rook, waits to cut straight through, his move delayed but decisive.

Watson, though seconds behind, is structurally near-equal: applying Holmes’s methods in the hall, proving that genius only holds weight through comparison. A weak Watsons flatten stories; a strong Watsons humanize them.

Even Mycroft, framed as Holmes’s supposed equal, is reduced to eccentric comedy, naked entrances and bureaucratic wit. The laughter isn’t neutral: it is the state stripped bare, clever but indifferent while pawns burn. Holmes spends pawns, Moriarty profits from them, and Mycroft chuckles on the balcony. The symmetry is always false; every figure above the pawns is complicit.

The bombings uphold the illusion. Anarchists are blamed, Simza’s brother scapegoated for chaos while the true architect profits. Disorder absorbs the cost so the balcony duel stays clean. The audience is meant to see two kings in balance while pawns vanish off-screen, their erasure explained away as radical noise.

Rules Shattered (The End of Gentleman’s War)

On the balcony, Holmes and Moriarty preserve the theatre of civility, moves spoken aloud, etiquette staged, respect performed. But the board is already blooded. Adler is killed out of turn. René is silenced by his own side. Mary is discarded in an efficient beat. Simza is written thin. Holmes’ collapse is recoded as eccentricity. The rules are invoked precisely because they no longer bind. His disguises, addictions, and sudden stillness are treated as quirks of genius, when they are really the language of grief.

Ritchie’s filmmaking itself shatters the poise of the period piece, trading candlelit restraint for rapid cuts, slow-motion ruptures, ballets of shrapnel. The Swiss train sequence shows it most clearly: a supposed gentleman’s journey shredded into fragments of etiquette-in-bullets, smoke filling the carriages, time dilated into brutal spectacle. The genre’s “rules” fracture in the cut before they fracture in the plot.

Two kings remain framed, as if the duel were equal. But the board shows what the factory floor hides: pawns erased, bishops cleared, the war reduced to ornamental faces. Smoke already names the field, recording absence in place of memory.

Holmes’ yellowface disguise underscores the collapse. Civility is not preserved but mocked, importing colonial caricature into the duel’s theatre, weaponizing stereotype as if it were another rule of play. What masquerades as clever costume is really a rule already broken, civility hollowed into performance.

The balcony, then, is just mask. A polite duel laid over mechanized slaughter. Factories forge rifles, bombs slip into carriages, men dangle from hooks as phonographs play.

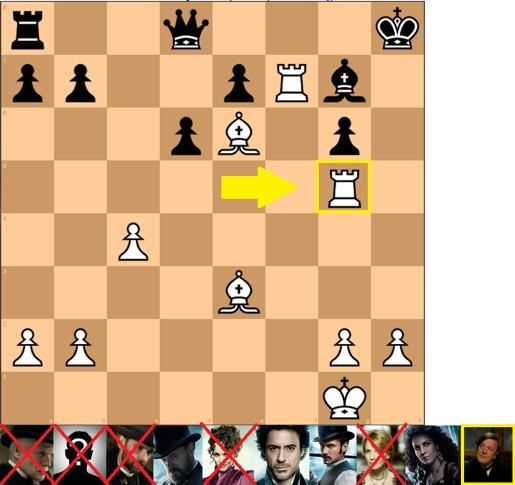

The War Machine Wins

Holmes seizes the notebook and plunges with Moriarty, but the balcony duel is ornamental. The real battlefield has already been revealed: the factory floor, gears pounding, smoke swallowing the faceless. The camera lingers on hooks and bodies, men suspended like pieces already cleared, industrial death framed as background texture. Pawns do not survive here; they are advanced for one move, then cleared.

Dr. Karl Hoffmanstahl was only the prototype, advanced for a surgical function, then erased. Holmes’ yellowface disguise belongs here too, a mask deployed for one beat, then discarded. The anarchists blamed for bombings meet the same fate, invoked as chaos so the machine’s true engineers remain unstained. Expendability scales from individual to collective, comedy to catastrophe. It is the same logic that would spill into 1914, when pawns were cleared by the millions in the name of alliances and inevitability.

The camera insists on whose survival matters. Holmes’ plunge is remembered, framed in slow motion, his calm face last in sequence. Moriarty is given panic, Holmes composure. The kings are staged as mythic figures while the factory floor, where thousands of pawns vanish without name, becomes faceless backdrop. Zimmer’s score swells for their duel, while the phonograph aria prettifies violence, drowning the sound of bodies clearing from the board.

The balcony romance of equals is only distraction. Beneath it the machine devours all, pawns, bishops, even kings when their spectacle is finished.

The Unreliable Player

The final sleight is narrative, not strategic. Holmes “returns” as a joke in a chair, resurrection staged as cleverness. A king is revived with a cut; pawns remain dead. Adler is not restored. Hoffmanstahl is not remembered. The yellowface disguise is not interrogated. The anarchists are not exonerated. The trick lands, the audience laughs, and the machine endures.

Chess allows a king to return with a single stroke of notation. The film does the same, Holmes resurrected in a cut, but pawns never come back to the board.

The frame congratulates itself for wit while leaving the pawns un-resurrected. Holmes’ reappearance proves only that narrative privilege belongs to the king. Pawns cannot be edited back into being.

Works Cited

Bent Larsen vs. Tigran Petrosian, Second Piatigorsky Cup (Santa Monica, 1966). A game whose moves prove more enduring than most governments.

Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011), dir. Guy Ritchie. An entertainment that insists on being both deduction and demolition.

Zimmer, Hans. Cimbalom, strings, and phonograph arias that conspire like accomplices.

Acknowledgements

I must thank my ever-present companion, Dr. Watson, who insists that mere mortals deserve notice in such affairs, and my brother Mycroft, whose bureaucratic interventions I mock while secretly relying upon. Additional gratitude goes to the archivists, theorists, and cinephiles who kept the board illuminated; without your candles, this essay would be smoke alone.

Disclaimer

Naturally, the views expressed herein are my own, not those of Scotland Yard, Her Majesty’s Government, or indeed Guy Ritchie. Any resemblance to historical arms syndicates, imperial scapegoating, or contemporary profiteers is, of course, entirely deductive. Should Moriarty lodge a complaint, I shall consider it further confirmation of accuracy.

wait this is so coool

I have been looking forward to reading this, and of course I am not disappointed! I love this so much! I’m a secret lover of chess and Holmes has always been a favorite of mine. My kids love it too, but they prefer the Gnome version of the tale lol

This is truly wonderful. Your translations always expand the scope of the films we know and love (or sometimes have never watched) 🖤