Renaissance Man

How Learning Becomes Belonging on Institutional Terms

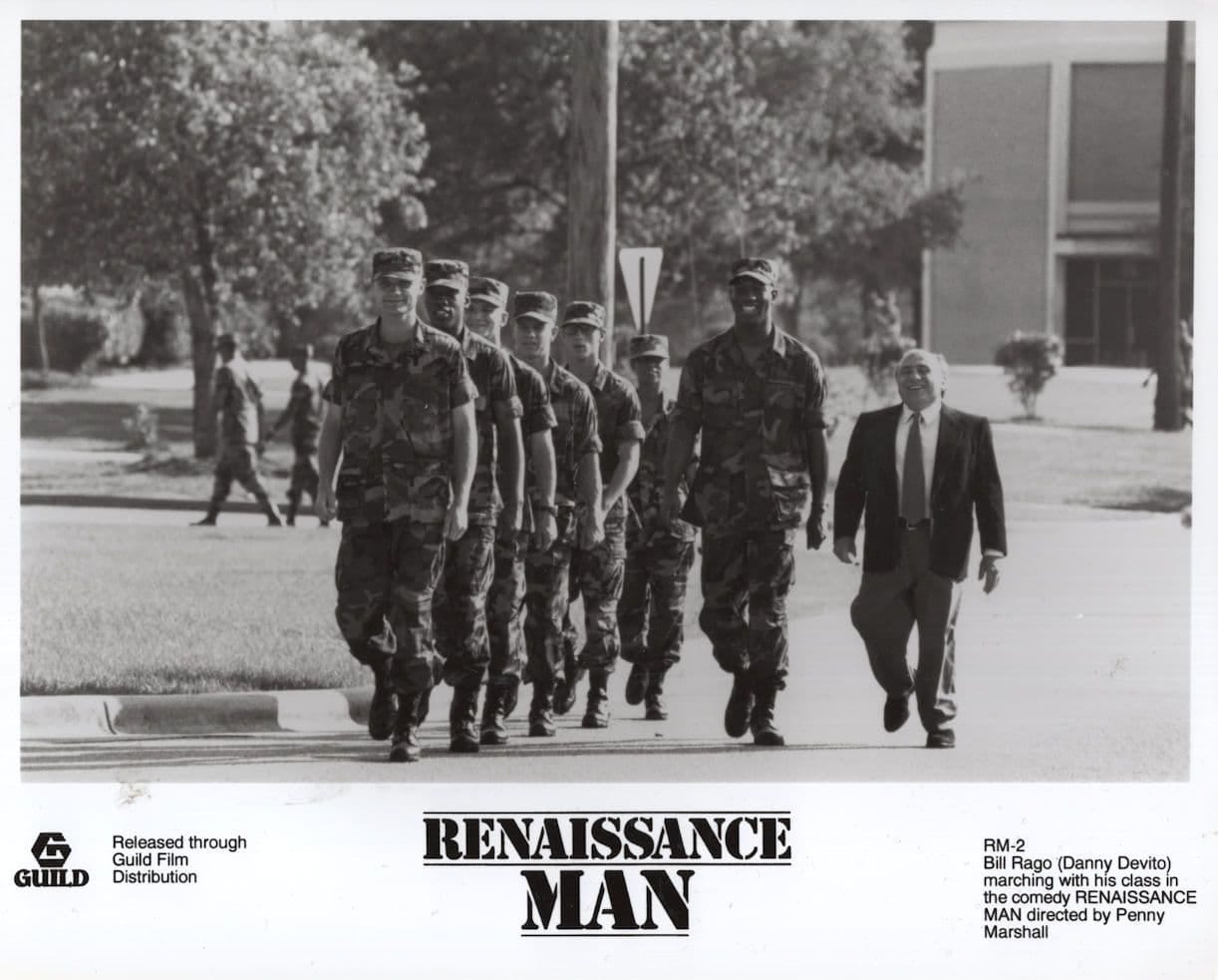

The first time I saw Renaissance Man, it was shown to us in school. Not as entertainment, but as something approved. A movie trusted to do quiet work in the background while the day moved on.

Renaissance Man presents itself as a modest story about second chances. A man between jobs, a classroom no one takes seriously, a curriculum chosen almost by accident. The miracle, we’re told, is that learning happens at all.

Nothing announces itself as important. Improvement arrives conversationally, the way advice does when it’s framed as a favor. You’re not being corrected. You’re being helped.

Rago doesn’t arrive as a disruption. He arrives as someone who can make the room work. He treats the situation as manageable before anyone asks what it needs. A little structure, a little confidence, something useful to get things moving.

Authority settles in without being requested. The classroom responds because there’s nothing here that sounds like a demand. Confidence sounds like help when it’s delivered smoothly enough.

The Narrow Canon

Rago doesn’t begin by teaching discipline. He begins by easing the room.

He chooses Hamlet, not a story that resolves doubt into unity or turns language into command. He doesn’t start with poetry or philosophy. He starts with sex, violence, intrigue. Ghosts. Murder. Betrayal. The hook is not enlightenment. It’s access.

Shakespeare enters as something practical. Something that travels. A tool that can move easily between people who have not been asked what they need, only whether they can keep up. The canon works here because it doesn’t arrive as a demand. It arrives as momentum.

Belonging, at this stage, doesn’t look like a rule. It looks like motion.

The classroom functions because nothing has been made heavy yet. No one is being tested. Nothing has to be proven. The text feels useful, and usefulness feels like care.

The movie trusts that ease will hold.

Authority on Loan

The recruits already know how to survive together. The language exists before Rago arrives. Teasing. Ritual. Call-and-response. He steps into a room that already functions.

Authority settles in because it doesn’t interrupt that rhythm. Rago borrows credibility by keeping things moving. Cass notices.

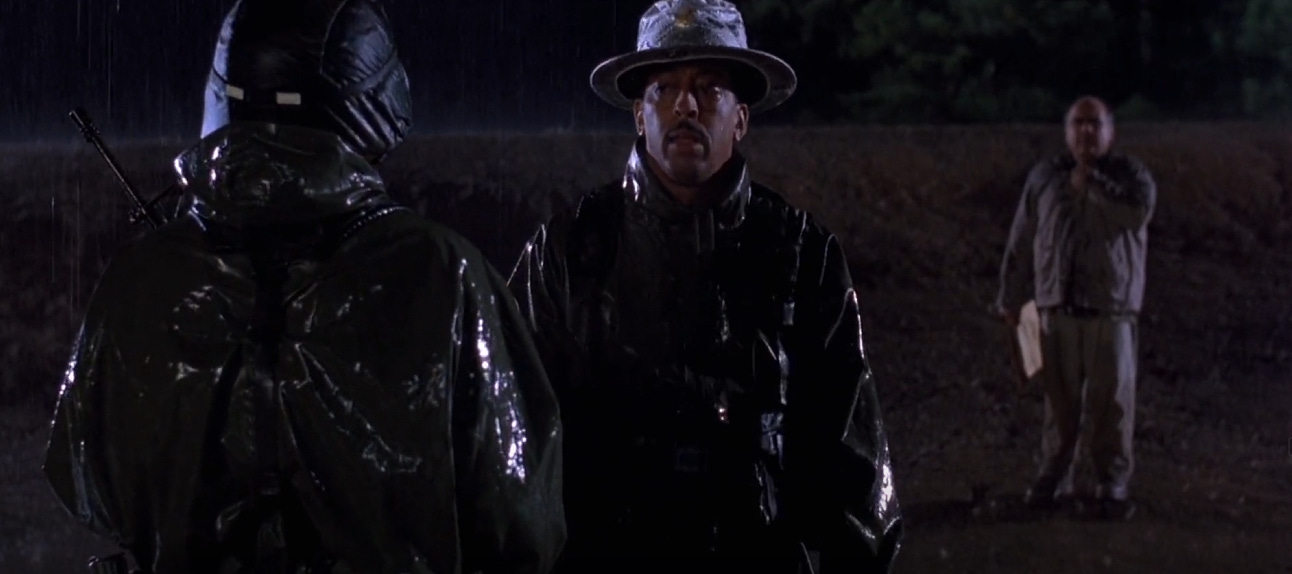

Sergeant Cass does not mistake ease for reliability. His authority is not conversational. It is continuous. Order is not cruelty. It is memory. The thing that holds when conditions break.

When Rago leaves for the interview, the absence registers immediately. The rhythm stutters. The trust he’s been borrowing doesn’t follow him out the door.

He returns with the same casual confidence, but the room is no longer offering it freely. Authority waits to see if he’s staying.

This is where Rago tells the Arlington story. Years earlier, he walked from Arlington Cemetery to the White House carrying the name of a soldier who died in Vietnam. He remembers the walk. He does not remember the name.

Proximity felt like responsibility. Effort felt like obligation fulfilled.

The logic holds. He steps closer.

Institutional Authorization

Rago does not harden. The institution authorizes him.

Captain Murdoch frames the situation cleanly. Schools failed. Homes failed. Teachers couldn’t hold them. The Army becomes intake. Not choice. Not design. Inevitable.

Murdoch’s analysis names debris, not architecture. Policy disappears. Structure dissolves. What remains is obligation.

Rago listens closely. This version of help flatters him. It recasts intrusion as duty.

Once he is allowed back into the room, Shakespeare changes function.

What entered as refuge becomes ritual. Henry V replaces Hamlet. Brotherhood replaces inquiry. The speech is no longer discussed. It is deployed.

When Benitez recites St. Crispin’s Day in the rain, it is not analysis. It is confirmation. He holds cadence. He proves alignment under pressure.

Cass listens. The test is passed.

Language no longer shelters. It organizes.

Assumed Moral Labor

Rago’s boundary crossing does not fall evenly. It finds the people already navigating risk.

Hobbs understands authority too well to invite it. He absorbs the material quickly and keeps his head down. He finishes lines under his breath. He lets knowledge pass without asking it to be named. When Rago notices him, Hobbs deflects. Lowers his voice. Keeps moving. This is not modesty. It is strategy. Hobbs knows that visibility attracts systems that do not arrive gently.

Rago reads that restraint as untapped promise.

He praises Hobbs anyway. Frames him as exceptional. Treats excellence like something that should be announced instead of protected. Hobbs never asks for elevation. He quietly resists it. That resistance is lost on someone trained to believe recognition is always a gift. Rago does not hear a boundary. He hears hesitation and pushes past it.

What Hobbs is hiding from is not failure.

It is extraction.

Jackson names it outright.

He talks about football without nostalgia. About how his body mattered and his mind didn’t. About being passed along without being taught anything that lasted. About a knee ending the only future anyone ever planned for him. He does not want that life for his son. He does not want his child reduced to a commodity that wears out. The Army, in his telling, is not freedom. It is the lesser machine.

Rago cannot stay with that discomfort.

Instead of letting Jackson’s grief stand, he pivots to uplift. Alberti. The Renaissance Man. A figure who was both strong and brilliant. A story that reframes structural harm as personal balance. Jackson is talking about escape. Rago responds with synthesis. Intelligence reattached to athleticism, not liberated from it.

It converts a racialized account of bodily use into a universal lesson about fulfillment. It replaces cost with inspiration. It keeps the machine intact by refusing to name what it takes.

This is the pattern.

Hobbs asks not to be seen and is made legible.

Jackson asks not to be used and is given a role model.

Both are harmed politely.

When Rago later intrudes on Davis’s behalf, the outcome is different. Davis does not ask for intervention, but the film rewards it. Records are found. Closure is granted. The breach produces resolution. One clean success reframes the earlier damage as necessary risk.

Two out of three don’t get that ending.

Rago never notices the ratio. He counts movement, not cost. He believes sincerity evens the ledger. The institution allows the belief because it only needs the one success to justify the rest.

The harm stays where it always was.

Quiet.

Absorbed.

Unevenly distributed.

Transformation as Assimilation

What makes the conversion work is not the argument.

It’s how good it feels.

There is a very pleasant discovery at the center of this stretch of the film: that a room doesn’t need a complicated theory to function. It needs a shared beat. There is something profoundly reassuring about bodies that move together, voices that answer on time, effort that resolves into sound. Disorder recedes. Friction smooths out. The work begins to feel lighter simply because it is synchronized.

This is where Gregory Hines changes the temperature of the movie.

Hines carries rhythm the way some people carry authority. Not by demanding attention, but by setting a tempo others want to follow. His tap background is not an anecdote. It’s an inheritance. Call-and-response doesn’t register as drill when he leads it. It feels communal. Cadence becomes music. Discipline sounds like joy.

The institution loves this version of order.

Rhythm is its most efficient language. It doesn’t require belief, only timing. Move together. Answer together. Trust the beat. Hines gives the film a body that makes this logic feel earned instead of imposed. Drill becomes dance. Chant becomes culture. Alignment stops looking like surrender and starts looking like expression.

The camera rewards him for it. The film does too. His ease and musicality are allowed to shine. Nothing about his performance is diminished. That’s the seduction. Black excellence isn’t merely tolerated here. It animates the room. It makes the process feel alive.

Hobbs’s quiet intelligence dissolves into the collective voice. Jackson’s fear for his son is absorbed into morale. Distinctions flatten into harmony. Individual histories blur into a rhythm that sounds correct. The pleasure of watching it work overtakes the question of what had to be absorbed to make it work this smoothly.

Even here, not everyone disappears completely.

In the middle of the music, an actor will hold a breath a beat too long. A look will linger just past the count. A pause slips through where the rhythm doesn’t quite close. It’s subtle. Easy to miss. But it’s there. The sound of a person still inside the body, not fully converted into tempo.

The film doesn’t dwell on these moments. Neither does the institution.

What it keeps is the rhythm. What it celebrates is the harmony. What it learns is that this kind of alignment doesn’t need force. It needs performers who make it feel good.

Rago takes this as confirmation. Look how alive they are. Look how well it works. Look how easily joy fills the space where resistance might have been.

He never asks what had to go quiet for it to sound that clean.

Innocence as Ideology

Rago is allowed to experiment.

He interrupts authority. He overreaches. He misjudges when to speak and when to stop. Each error is absorbed. Each breach is reframed as sincerity. Curiosity. Heart.

The recruits do not receive this protection.

They must execute perfectly. They must move correctly. They must speak on time. When they falter, consequence arrives immediately and visibly. There is no margin for confusion.

Rago teaches Hamlet, a text full of doubt and delay. He is never asked to resolve it. He never has to perform it under pressure.

The recruits are asked to perform Henry V. Certainty. Unity. Sacrifice. They must carry the words cleanly, in formation, on command.

Innocence absorbs error for one body.

Brilliance is demanded from the others.

The Wrong Beat for the Right Decade

Hobbs is escorted out in formation.

The warrant is real. The name is already written. Rago is present but powerless. The camera does not linger.

The music does not pause either.

A rap track begins to play over Hobbs’s removal. The lyrics do not accompany the image. They speak over it. Street cadence reframes institutional consequence as personal fate.

The song is Marky Mark’s “Life in the Streets.” The music video shows a man selling drugs, chased by police, and funneled into military recruitment. The film gives Hobbs’s backstory to Marky Mark to perform.

What the movie cannot show inside its own frame, it outsources. Hobbs’s interiority becomes someone else’s performance.

In the early nineties, this sound was not neutral texture. It carried refusal. Memory. Critique. Here, it carries closure.

The beat finishes the work the system began.

Years later, the pattern will be compressed into a single cold line. A joke about culture borrowed until it sounds earned.

“To get played on screen by Marky Mark.”

The formation holds. New recruits arrive.

Sound is easier to carry than thought.

I wrote this because I keep thinking about what we call help, and who gets to define what it’s for. If it stays with you, I’m around in the comments.

Works Consulted

Renaissance Man (1994), directed by Penny Marshall

Screenplay by Jim Burnstein

Touchstone Pictures

Referenced cultural materials appear only as depicted or excerpted within the film:

Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Shakespeare’s Henry V (St. Crispin’s Day speech)

“Life in the Streets” — Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch (1991), referenced for critical analysis of sound and cultural framing

No external academic sources were used. All claims are grounded in the film’s structure, sequencing, dialogue, performance, and audiovisual language.

Acknowledgements

This essay exists because Bea suggested Renaissance Man.

I hadn’t thought about the film in years. What I remembered was charm. Warmth. The satisfaction of competence being recognized. What I had forgotten, or maybe never fully examined, was the cost structure underneath that feeling, and who gets to step away from it unchanged.

That reminder mattered. Not because it made me dislike the film, but because it helped me remember what I did enjoy about it: its confidence, its ease, its belief that care can arrive conversationally. This essay is an attempt to sit with that enjoyment long enough to see what else moves with it.

Thank you, Bea, for the nudge, and for trusting that I’d take the movie seriously.

Disclaimer

This is an independent critical essay.

Renaissance Man (1994) is owned by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures and distributed by Touchstone Pictures. All characters, dialogue, and audiovisual materials are the property of their respective rights holders.

This essay is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or produced in association with Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, Touchstone Pictures, or any related entities.

Film stills and brief excerpts are used under fair use for the purposes of criticism, commentary, and analysis, in accordance with U.S. copyright law. No copyrighted material is reproduced beyond what is necessary to support critical discussion.

Interpretations reflect the author’s reading of the film’s internal logic, structure, and formal choices. Reasonable viewers may experience the film differently, including with affection, gratitude, or nostalgia. Those responses are not dismissed here.

Forgot all about this one. This and Major Payne!!

This is amazing! Thank you so much for adding this film to your list of wonderful projects.

This movie means so much to me for reasons that have very little to do with the actual film. It was the spark that lit the fire of my love of Shakespeare, which lead me down the road to loving poetry. But more than that, it opened my eyes to imbalances that I hadn’t recognized before. It made me ask questions about how things worked and why. I was around 8 the first time I saw this film, and my aunt said it would be “too complex” for me to understand lol but I sat through every moment and fell in love with the “picture within the picture”.

As expected, you painted that picture beautifully. 🖤